Bad Bunny, Breakfast Cereal, and the Art of Being Different

One of the most enjoyable classes during my MBA was Industrial Economics by Robert Pindyck. We studied how companies use strategies like bundling and brand proliferation to dominate markets and keep competitors out. The examples were things like Kellogg's, Microsoft Office, and the breakfast cereal wars of the 1970s.

Last night, I watched Bad Bunny perform at the Super Bowl halftime show, and all I could think about was cereal.

Let me explain.

The Cereal Wars

In the 1950s through the 1970s, four companies, Kellogg, General Mills, Post, and Quaker, controlled the American breakfast cereal market. Their strategy was ruthless and elegant: launch so many cereal brands that there was simply no room for anyone else.

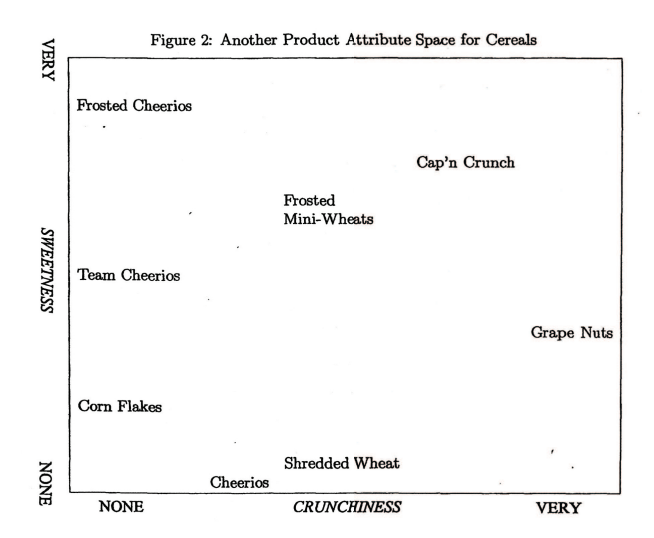

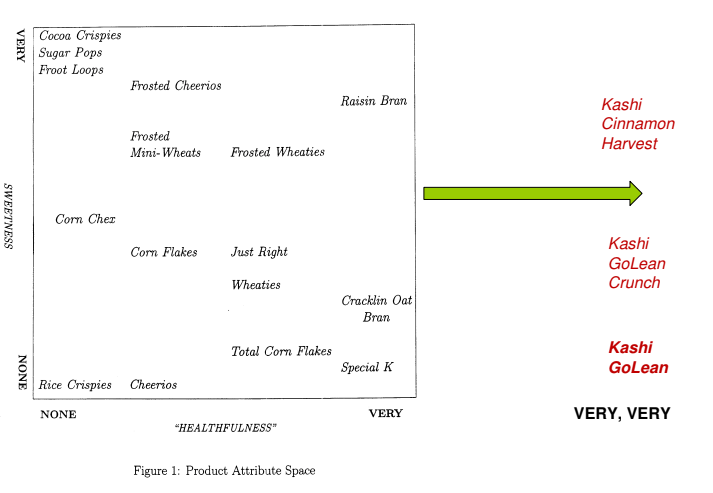

Think of all cereals positioned along a spectrum. On one end, super sweet (Cocoa Puffs, Froot Loops). On the other, "healthy" (Special K, Grape Nuts). Crunchy versus soggy. Kid-friendly versus adult. Every possible combination of taste and positioning was occupied by an existing brand from one of these four companies.

This is what economists call product attribute space. And the strategy of flooding that space with brands is called brand proliferation.

Here's why it works: each new cereal has a high fixed cost to launch: R&D, packaging, advertising, and "slotting allowances" (essentially paying supermarkets for shelf space). If you're a new company thinking about entering the market with a new cereal, you look at the shelf and realize that no matter where you position your product, there's already a well-funded competitor right next to you. The math simply doesn't work. You can't recoup your investment.

The four cereal giants knew this. They didn't need to lower prices or play dirty. They just needed to leave no gaps.

For decades, it worked. New entrants were virtually nonexistent, and the incumbents enjoyed some of the highest margins in the food industry.

Then Came Kashi

In the 1970s, a small company called Kashi did something the big four hadn't anticipated. Instead of trying to compete in the middle of the attribute space — where every position was already taken — they went to an extreme.

Kashi positioned itself as a "natural" cereal. Not just "healthy" like Special K (which was still a processed product from Kellogg). Kashi was actually different: whole grains, no artificial anything, a product that looked and tasted nothing like what was on the shelf. It was so far out on the attribute spectrum that the incumbents couldn't credibly follow. Kellogg couldn't just slap a "natural" label on Frosted Flakes. The brand wouldn't allow it.

Kashi found the gap that wasn't supposed to exist.

This is the key insight from the theory: brand proliferation works as long as the attribute space is finite and the brands are immobile — meaning, once you position a brand, you can't easily move it. Cocoa Puffs can't become a health food. And when someone finds an extreme position that incumbents can't reach, the whole strategy breaks down.

Now, Think About Music

Music has its own attribute space. You can map artists along dimensions like genre (pop, hip-hop, reggaeton, rock, salsa), production quality (polished mainstream versus raw/underground), and persona (rebellious, wholesome, vulnerable, intellectual).

For decades, three major labels — Universal, Sony, and Warner — have played the same game as the cereal companies. They sign artists across every genre, invest heavily in marketing and distribution (the "fixed costs" of the music industry), and use their leverage with radio stations and streaming playlists to crowd the space.

The fixed cost of launching an artist used to be enormous: studio time, music videos, radio promotion, tour support. This was the music industry's version of slotting allowances. If you were an independent artist, the math didn't work; just like trying to launch a new cereal against Kellogg.

But something changed. Recording costs collapsed. Distribution became essentially free through platforms like Spotify, Apple Music, and YouTube. TikTok turned into a discovery engine that bypassed the gatekeepers entirely.

The "F" in the economic model (that fixed cost that made entry impossible) suddenly got much, much smaller.

And that opened the door for a Kashi-type move.

Enter Bad Bunny

When Bad Bunny first appeared on the scene, he was the musical equivalent of Kashi on the cereal shelf.

If you had never heard of him and someone played you one of his early records, your reaction would likely be one of two things:

- "What the hell is this? I can't understand anything he's saying. I've never heard anything like it. I don't like it."

- "This is vastly different from everything else out there."

That second reaction is the one that matters.

Bad Bunny didn't try to compete in the middle of the music attribute space. He didn't make polished pop or conventional reggaeton. He created something that borrowed some elements from reggaeton and Latin trap, but combined them with an unconventional vocal style, a genre-fluid production approach, and a persona that was unapologetically Puerto Rican, irreverent, and weird.

He went to the extreme of the attribute space; a position that major labels hadn't occupied because they couldn't. You can't manufacture authenticity. A label executive trying to create a "Bad Bunny type" would produce something polished and generic, which would defeat the entire point.

This is exactly the Kashi playbook.

But Here's Where Bad Bunny Went Beyond Kashi

Kashi stayed in its corner. It was a natural cereal for health-conscious people, and that was that. It worked, but its growth had a ceiling.

Bad Bunny did something more sophisticated. He didn't stay in his extreme corner; he expanded through the attribute space, systematically.

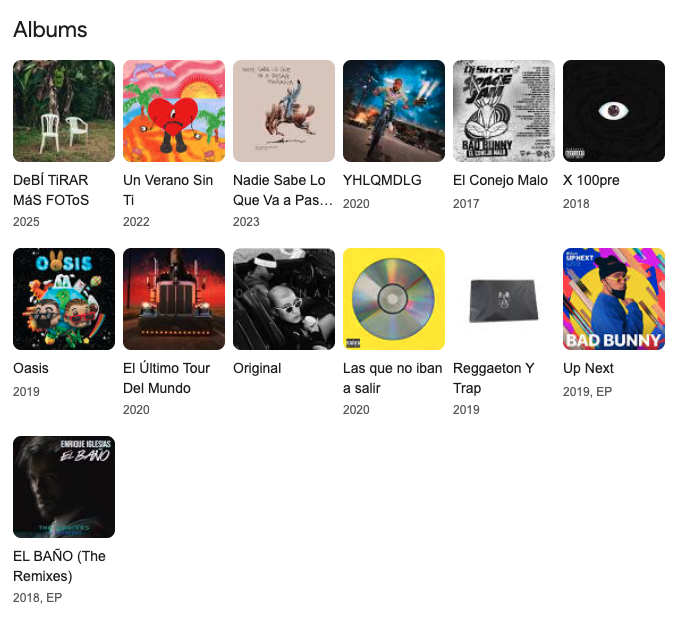

He started mixing other popular genres into his music. Salsa. Merengue. Indie rock. Dembow. Each addition brought new listeners into his orbit. His most recent album, DeBÍ TiRAR MáS FOToS, dove even deeper into Puerto Rican folk traditions like plena and bomba; genres that his older listeners grew up with but never expected to hear from a reggaeton-adjacent artist.

According to the economic model, this shouldn't work. Brand immobility says you can't reposition — just like Cocoa Puffs can't become a health cereal. But Bad Bunny pulled it off because he didn't reposition. He expanded. Each genre addition was filtered through his distinctive voice and persona. It was always "Bad Bunny doing salsa," not "a salsa artist." The core brand remained the anchor while his radius in the attribute space kept growing.

And here's the really clever part: those catchy, sometimes irreverent phrases ("Tití Me Preguntó," "Yo Perreo Sola"), along with his distinctive vocal delivery that people love to imitate, created a form of consumer lock-in. Once you're humming his songs or mimicking his style, switching to a competitor feels different. It's the musical equivalent of brand loyalty.

The Super Bowl: Distribution at Scale

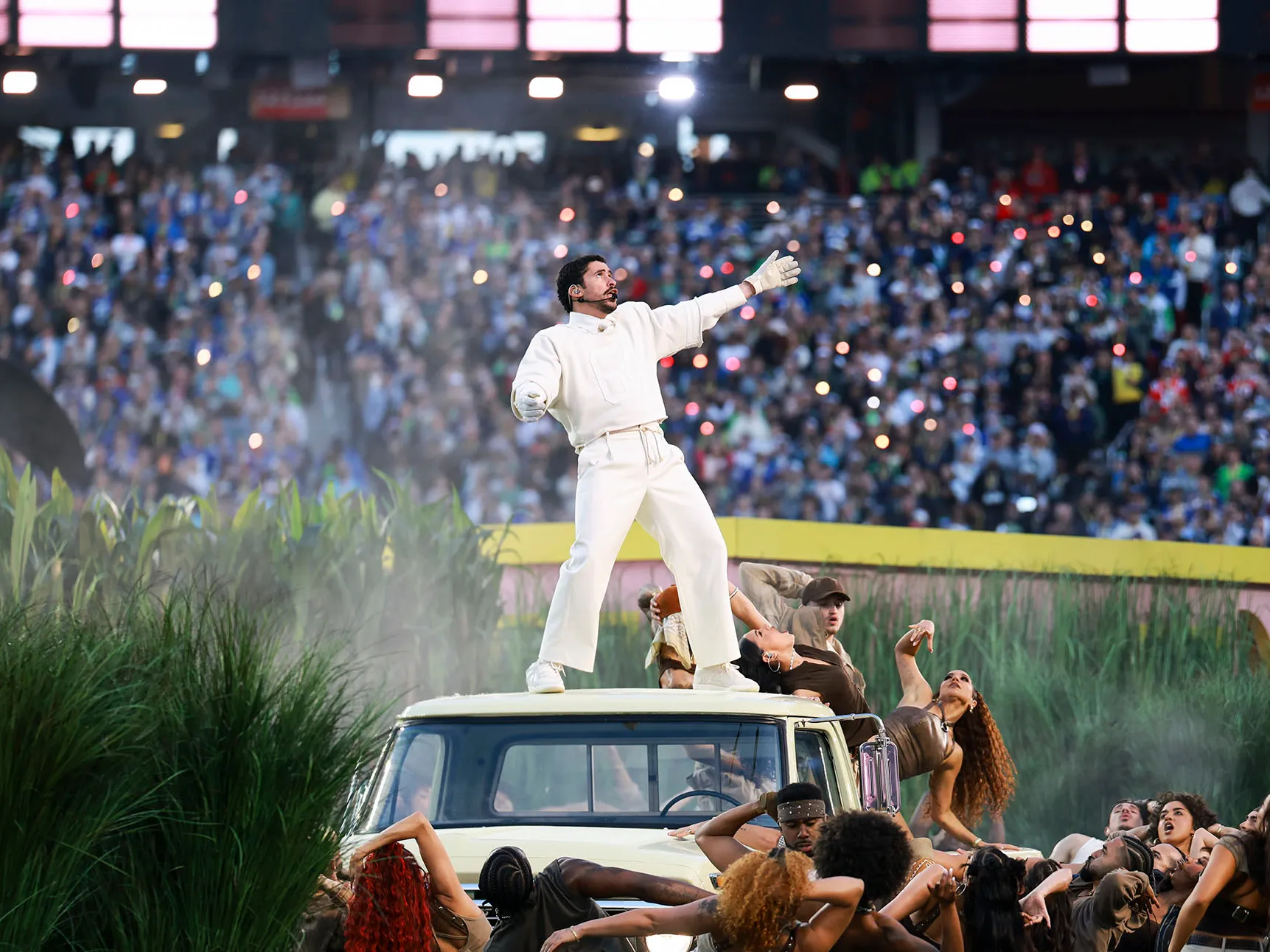

Last night's Super Bowl performance was the culmination of this strategy.

Bad Bunny performed entirely in Spanish on the biggest stage in American entertainment. He opened with "Tití Me Preguntó," brought out Lady Gaga and Ricky Martin, staged an actual wedding on the field, and ended by climbing a power line, a reference to Puerto Rico's ongoing electricity crisis.

In business terms, the Super Bowl was a massive, one-time reduction in the discovery cost barrier. It's the equivalent of getting free shelf space in every supermarket in America simultaneously. For someone who already had the product and a loyal base, but faced an awareness ceiling with non-Latino and older American audiences, this was the moment where his reach expanded to the entire market.

Think about the generational bridge. Older listeners... people like me, whose musical tastes were largely set in the '90s and 2000s, didn't come to Bad Bunny because reggaeton suddenly improved. We came because he built a bridge using genres we already knew and liked. When he layers salsa or plena into his music, he's not just expanding his attribute space, he's expanding the total market. He's bringing people in who would never have entered the reggaeton-adjacent space otherwise.

When he told critics before the show, "People only need to worry about dancing... there's no better dance than the one that comes from the heart" he was essentially saying: I don't need to reposition to your preferences. I'll bring you to mine.

What This Means

Bad Bunny won Album of the Year at the Grammys just one week before the Super Bowl... for an album recorded entirely in Spanish, rooted deeply in Puerto Rican folk traditions. That album made him the most streamed artist on Spotify in 2025, with 20 billion streams.

He didn't achieve this by playing it safe or competing in the middle. He 1) found the extreme position that no one else could credibly occupy, 2) expanded systematically without losing his identity, 3) created switching costs through cultural connection and catchiness, and then 4) used the biggest stage in American entertainment to eliminate the last remaining barrier: awareness.

The cereal companies spent decades keeping competitors out by leaving no gaps. Bad Bunny succeeded by proving that the most powerful position in any market isn't in the middle... it's at the edge no one thought to reach.

Comments ()